Serverless Distributed Cron System

I’ve implemented the following in a very untested project I have decided not to release, but the mental exercise of going through the system is worth doing.

What is Cron? (baby don’t hurt me)

Cron is a generic name for various schedulers that run commands at a specific interval. Many developers encounter it via a crontab file or similar that they have to edit. Here is an example (with a neat graph from wikipedia):

┌───────────── min (0 - 59)

│ ┌────────────── hour (0 - 23)

│ │ ┌─────────────── day of month (1 - 31)

│ │ │ ┌──────────────── month (1 - 12)

│ │ │ │ ┌───────────────── day of week (0 - 6) (Sunday to Saturday;

│ │ │ │ │ 7 is also Sunday)

│ │ │ │ │ ┌────────────the command you are going to run (should be executable)

│ │ │ │ │ │

5 2 * * 6 /var/lib/scripts/awesome-script.sh

It’s pretty nifty, and fairly easy to automate. Lots of developers seem to want to write versions in their own languages (because why not!), and here is a list of awful implementations in various languages. If you aren’t listed here, don’t worry, your version is almost certainly also awful.

- Java: cron4j

- Node.JS: later and node-cron

- PHP: this cron library and laravel’s sceheduler

- Python: plan

- Ruby: rufus-scheduler and whenever

There are certainly others, these are just the ones I knew off the top of my head or googled really quickly. They are probably fine projects, just that re-implementing cron for the hell of it seems like a waste of time.

For the record, here are the components of a reasonable cron scheduler:

- A scheduler (cron)

- A process to retrieve logs and process results (cron/syslog)

- A mechanism for storing the tasks (your cron file)

- A ui for editing cron tasks (your text editor of choice)

Distributed Cron

This is a pretty nasty problem. It turns out that building distributed systems is hard, and the semantics around running cron tasks don’t necessarily work for every problem.

- You may want to ensure only one version of a command is running at a time.

- You may want to ensure every invocation of a command is handled.

- You may want to ensure every task completes successfully.

- You may want to log all output somewhere for later investigation.

- You may want to be able to pause a command from being scheduled.

- You may want to stop a run that is currently executing.

- You may want to place commands in maintenance mode.

- You may want to group commands for easy perusal in large installations.

- You may want to lock down commands to certain groups of users.

- You may want to be able to schedule commands via both an api and web ui.

- You may want to notify on errors.

- You may be dealing with commands that have an exit code of

0but actually failed. - You may hope that you won’t need to learn entirely knew ways of thinking in order to manage this system.

There aren’t really too many ways to “properly” do distributed cron. You can hack it pretty easily using a MySQL based system for scheduling jobs, as noted by Quora in this blog post. It works, but isn’t the greatest thing in the world, as you are probably also using MySQL for your queuing system (lulz).

At work, a hackathon project turned into CronQ, our distributed cron solution using MySQL and RabbitMQ. Now we have THREE systems to keep highly-available! Turns out it works - using like 4 processes, one to inject jobs, one for running jobs, one for gathering results, and one for an ok ui - but certainly doesn’t have all of the above things built-in. Also, as a by-product of using MySQL, the developer interface is this terrible ISO 8601 Interval format. Even I have trouble explaining how it works to developers, and I maintain the thing.

At the webscale end of this problem, you have Chronos. It’s pretty awesome, is built on Mesos, and is webscale af. But you probably don’t want to run all that just so your rinky-dink cron task doesn’t not execute when the only host it is on goes down. If you have Mesos, awesome, try it out. I don’t, and I also don’t think it’s a good use of my time to maintain.

You could also:

- wrap every command with your favorite locking mechanism of choice - consul is distributed and you might have it up, but I’ve seen a ton of Redis or Postgres usage here

- place the same crontab on every file

- hope for no network partitions

Good luck? Hope you’re using a service like cronitor.io to monitor your jobs.

Serverless Cron

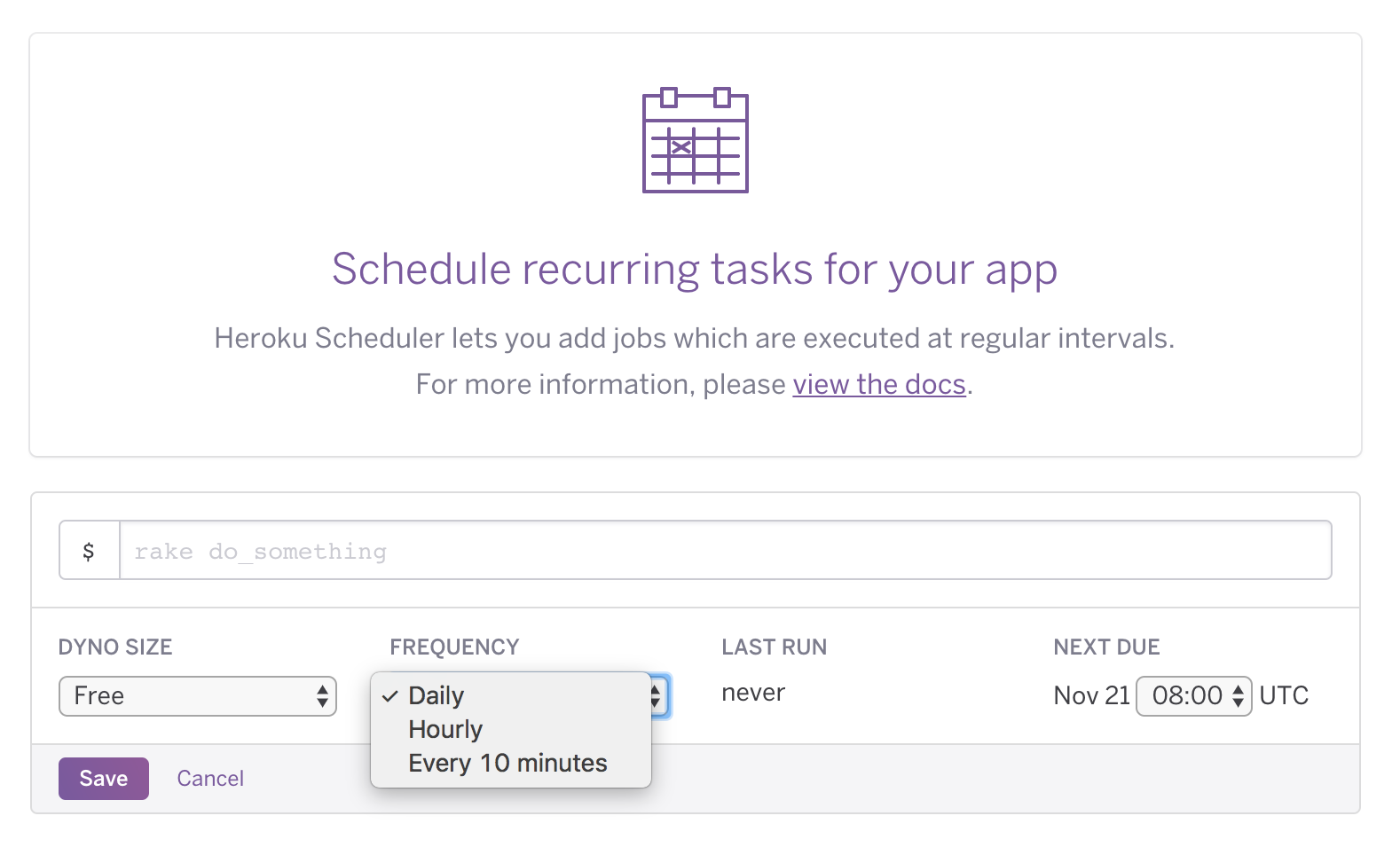

Heroku has a pretty nice scheduler. Here is a screenshot!

It’s also very barebones. You can add a command, set one of three frequencies, and more or less hope for the best. Still, pretty useful for developers. They don’t really need to think about much except for the command itself.

AWS Lambda has a similar feature. You can schedule based on one of two syntaxes:

rate: Thinkyearlyorhourly. Rates are pretty useful if you want to not need to decipher when your cron syntax says something will run. The heroku dashboard gets this right I think, and I believe rate will continue to be pretty powerful.cron: This is the syntax we all know and love to lookup every time we write it.

Lambda, however, has a few limitations:

- You can only execute code in lambda. You cannot execute code on other servers, at least not directly (webcron? lol).

- By default, you can only execute 100 functions at a time. You can have this raised, but you probably don’t want to break other uses of lambda in your system.

- The deployment environment is pretty limited - Java, Node.JS, Python - unless you use a shim, which is less than ideal.

Still, it’s a pretty useful primitive for building on top of.

Distributed Serverless (mostly) Cron

Components?

- Lambda Scheduler Function

- Lambda Results Retriever Function

- Lambda DynamoDB Pruning Function

- Cloudwatch

- DynamoDB

- SQS

Jobs are stored in a DynamoDB table. This table can be hand-edited in the AWS Console for now, but in the future, you’d probably build some sort of Web UI (and API) on top of it. Here is what you would store:

- Group identifier for the command

- Name of the command

- Command

- Cron syntax specifying the interval at which to run

- Whether the command is enabled or not

Execution events are also stored in DynamoDB. Whenever a task is:

- Scheduled

- Started

- Completed (fail or success)

An entry is stored in the execution table. The entry has a reference to the original job, the current timestamp, position in the workflow, and any metadata (such as the executor and the exit code). This can be used at a later date to construct a history of runs for the job.

There is a Lambda function that is executed which prunes the executed events DynamoDB table. You probably don’t care about whether the command executed three months ago, so storing only relevant recent data here is important.

Aside: MongoDB’s capped collection functionality would be pretty useful in this situation, as then its somewhat fire and forget.

Lambda can execute a function every minute. Even with a 10 second start-time overhead, that gives us roughly 50 seconds to schedule tasks for that minute interval. Each iteration will:

- Retrieve all tasks from DynamoDB

- Throw away any tasks that do not need to be executed in that minute interval

- Enqeue a message (with a unique identifer for the job run!) into a group-specific SQS queue

Next, you have the actual task runner. This can be any old daemon that lives on your server. It simply listens for jobs on SQS and executes them. You can have a few different running modes:

- One at a time: Each task runner can execute one job at a time. If another job appears on it’s queue, it’ll ignore it until it’s current job is fulfilled.

- Resource-based: You could probably associated each job with an amount of resources it needs in order to be executed. With a bit of work, the task-runner can be made aware of what resources are left on the server, and appropriately retrieve a job to execute next. Users of plain-old-cron probably don’t care about this, but those living in highly available worlds might want to build this into their task runners (lol you’re also probably building something akin to Mesos at this point, so just use Chronos).

- Free-for-all task runners: Each task runner in a group will just continue trying to get a job from the queue. If it gets a job, it just starts it, OOM-killers be damned. Most developers sort of expect this behavior, though I believe the “One at a time” behavior is a bit easier to predict.

Why do we have task runners on actual servers? Personally, I like being able to execute the full range of code in my repositories. At work, we deploy the following languages in production:

- C#

- Golang

- Node.JS

- Ruby

- PHP

- Python

- Ruby

- Scala

Hell, there’s even a bit of Perl and Lua running around (don’t ask). Each system has it’s own tasks we want to run on a schedule, and usually on “actual” hardware. For traditional, non-container based systems, the tasks should run on the servers where a codebase is deployed, so it makes sense to have a task runner.

The task runner is responsible for the following:

- Executing a task: A subprocess will likely work here. You can get fancy and orphan a process, then poll for it’s file descriptor if you wish.

- Collecting logs: You can ship logs to cloudwatch if that is all you have handy, which gives you a shitty web ui for looking at logs. You may also want to integrate with your syslog solution of choice, such as the ELK stack or Graylog.

- Sending execution event notifications: Starts, Stops, Exit Codes, Host information etc. All of this should be recorded for later inspection.

Finally, you’ll have your Lambda function that retrieves results from a results queue and stores them in your execution events DynamoDB table.

Implementation Notes

The simplest solution here is to use python as your Lambda deploy target. It is supported, has a wide range of libraries, and is easy enough to deploy. Here are a few libraries you can use for your implementation:

- boto3: Because you’ll need something to both read and write to SQS.

- croniter: For parsing cron syntax in python. It’s the best library I found.

- delorean: You’ll need this to properly parse datetimes in the correct timezone (use UTC please).

- envoy: For dealing with python subprocesses. It’s honestly not so bad to do directly, but you really need to know what you’re doing or you’ll do something silly with log messages or file descriptors.

- flywheel: Works well for interacting with DynamoDB in an ORM-like interface.

- sh: In case you hate envoy for subprocesses.

If you wish to go the Golang route - which I would probably prefer, given that you can ship a binary for the task runner - you should look into the following:

- aws-lambda-go: You need a wrapper to deploy golang to Lambda, and this was the nicest thing I found.

- cronexpr: Well-tested cron parsing

- dynago: A surprisingly good way to interface with DynamoDB

- goamz: SQS

Closing Thoughts

At the end of the day, this is a system you are now maintaining. I highly suggest open sourcing it and being as loud as possible about how it works and how awesome it is (or isn’t) so that you’re not the only one looking at the code.

This system also doesn’t track dependencies and the like. It’s a straight reimplementation of cron, but for “the cloud”. If you need more, you’ll need to either write that other bit, or simply go to a system like Chronos or Luigi.

The above system did not describe any sort of reasonable web ui for tackling the developer experience problems. Bring in someone from your frontend team to work on that part, and be nice to them when they want to build an asset-pipeline for it. You reimplemented cron and your implementation is awful, you have no right to complain.

The task runners are going to be a bit of work. Things like waiting on new jobs to appear on the queue, properly handling subprocesses, and managing where logs go after they are collected will be a bit painful. Be sure to test any “performance” enhancements you implement first on a “toy” system before rolling it out into production and killing the distributed cron.

One last thing: Give credit where credit is due. The folks who have written the underlying libraries, frameworks, and infrastructure primitives have put you in a good position to succeed. If you’re filing a bug, try and also come up with a patch. OSS is a two-way street.